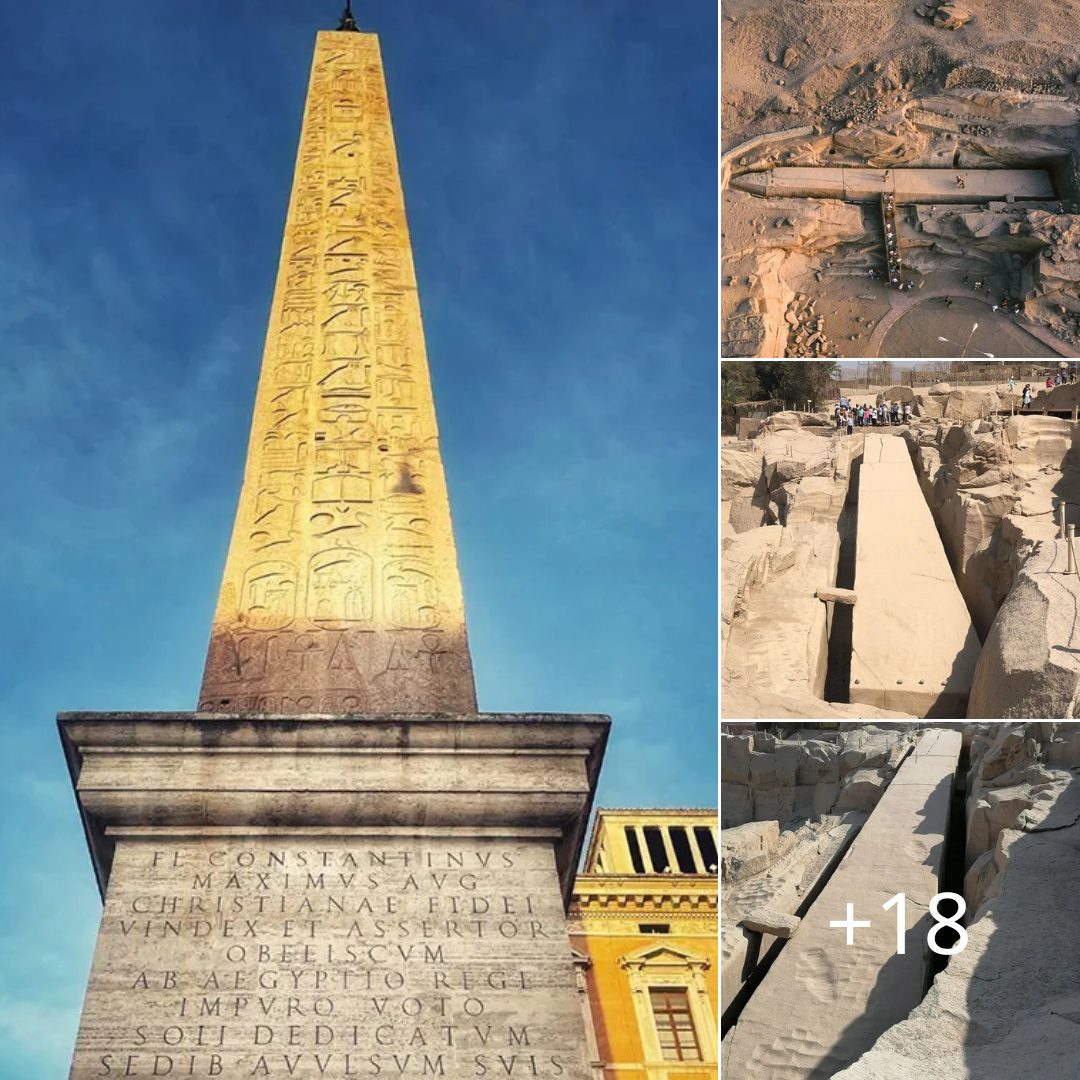

Durante las excavaciones en curso en la extinta ciudad de Çatalhöyük, en Anatolia, de 9.000 años de antigüedad, en el centro de Turquía, un equipo de arqueólogos descubrió algo notable. Mientras examinaban el esqueleto de un joven recuperado de un antiguo entierro colectivo, los arqueólogos encontraron un pequeño agujero perforado en el cráneo de este individuo, lo que demuestra que se había sometido a un procedimiento quirúrgico radical conocido como trepanación.

Desarrollada por primera vez durante el período Neolítico (10.000 a 4.500 a. C.), este tipo de cirugía se utilizaba para drenar líquidos o aliviar la presión sobre el cerebro. La trepanación era popular en muchas sociedades neolíticas de diferentes partes del mundo y los curanderos antiguos la recomendaban como forma de tratamiento para una amplia gama de lesiones y afecciones cerebrales, incluidos dolores de cabeza, conmociones cerebrales e incluso trastornos de salud mental.

Los arqueólogos que analizaron los restos óseos encontrados en Çatalhöyük encontraron evidencia de cirugía de trepanación. ( Agencia Anadolu )

La antigua ciudad de Çatalhöyük revela sus secretos de trepanación

Under the leadership of Anadolu University archaeologist Dr. Ali Umut Türkcan, a large team of researchers from several Turkish institutions have been busy performing excavations in residential areas of Çatalhöyük since 2020.

In 2022 the researchers unearthed a new residential area on one of the settlement’s sloping areas. Inside one house they uncovered a grave beneath the floor that contained seven skeletons. There was nothing especially remarkable about this, as it was customary practice in ancient Çatalhöyük to bury the dead under their previous residences, or under the homes of their loved ones.

But upon further examination, the researchers found a most unusual feature on the skull of one skeleton, which was eventually identified as having belonged to a young male aged between 18 and 19 who lived about 8,500 years ago. This was a small, round opening that was so neatly cut that it was clear it had not been created by an accidental head trauma.

“A round bone piece, approximately 2.5 centimeters [1 inches] in diameter, was removed from the side of the skull with a properly opened circular section,” Dr. Handan Üstündağ, an archaeologist from Trakya University, told an interviewer from the Turkish news agency AA. “During this time, we encountered many incision marks showing that they scraped the scalp. We think that this was a trepanation performed for therapeutic purposes.”Dr. Üstündağ explained that trepanation had already been in use for quite some time in ancient Anatolia before it was used by the people of Çatalhöyük. “The example we found in Çatalhöyük is one of the oldest,” Dr. Üstündağ said, before noting that “examples of practices that are at least 1,000 years older than Çatalhöyük were found in the excavations of Aşıklı Höyük, located near Kızılkaya village in Aksaray, and Çayönü Mound, in Ergani district of Diyarbakır.”

Nevertheless, this find was still incredibly significant, as it represents the first clear example of trepanation discovered in Çatalhöyük. “Our finding shows that people who lived 8,500 years ago tried to treat diseases, relieve the pain or suffering of their relatives, and prevent deaths,” Dr. Üstündağ stated.

Unfortunately, this treatment doesn’t seem to have done the man much good, perhaps because it was applied too late. “There is no indication that the individual was alive after the operation in question,” Dr. Üstündağ confirmed. “Because there was no sign of healing in the bone tissue. When this operation was performed, this person was either about to die or had already passed away.”

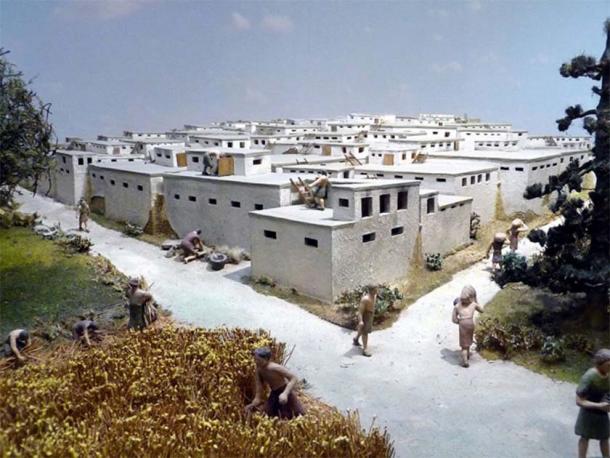

Model representation of Çatalhöyük in Turkey, at the Museum for Prehistory in Thuringia. (Wolfgang Sauber / CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Amazing Story of Çatalhöyük, Turkey’s Most Legendary Ancient City

The densely populated Çatalhöyük represented one of Anatolia’s earliest experiments in city building and urban living. The buried ruins of this UNESCO World Heritage site are located on the Konya Plain in Turkey’s Central Anatolian Plateau, not far from the modern city of Konya.

The latest estimates are that Çatalhöyük was occupied for at least 1,300 years, from 7,500 to 6,400 BC, which in Anatolia spans the Late Neolithic through the very earliest Chalcolithic or Copper Age periods. The settlement as a whole covered an impressive 34 acres (14 hectares), and includes an eastern mound that was occupied during the Neolithic and a western mound that housed city residents in the later Chalcolithic.

While this proto-city may have been home to as many as 10,000 residents during its Neolithic Period heyday, its architecture and design style bear little resemblance to modern cities of any size. Çatalhöyük was comprised entirely of private mudbrick homes and other multipurpose domestic buildings, which were relatively uniform in height.

These structures were packed so closely together that they created a honeycomb-like physical profile, as if they were one large structure with many conjoined parts. Homes were either directly connected to each other or accessible from one to another by ladders, and there was actually no room for footpaths or streets at the ground level.

All the evidence suggests that the people of Çatalhöyük were united by an egalitarian outlook, which rejected differences in status based on gender or wealth. Important tools and supplies were shared equally, and communal gatherings would have been frequent and would have included feasts prepared by community members using community-owned hearths or ovens.

With no physical boundaries separating homes people could have visited their neighbors easily, either by hopping from roof to roof (the rooftops in Çatalhöyük were flat and used as patios) or by crawling down ladders to enter other residence via side doorways. It is likely that family groups lived side by side, helping to preserve a sense of kinship that would last for generations. They also buried their deceased beneath their homes, maintaining those familial bonds even after death.

The residents of Çatalhöyük were deeply unified by their culture and religion. They decorated the walls of their mudbrick buildings with vivid murals, which included images of domestic, agricultural or hunting scenes in some instances and more stylized portrayals of animals or human-like figures that likely had spiritual significance in others. They also carved or molded striking figurines from minerals or clay, in the likenesses of humans or gods (female deities were portrayed far more frequently than male deities, which once fueled speculation that Çatalhöyük was governed as a matriarchal society).

Archaeologists sorting skeletal remains found at Çatalhöyük. (Anadolu Agency)

El arte perdido de la trepanación, una innovación médica neolítica

Como demuestra el descubrimiento del cráneo de un adolescente con un agujero de trepanación, los habitantes de Çatalhöyük también practicaban la medicina, lo que demuestra otra característica asociada con el verdadero desarrollo social. No se sabe si hubo médicos o cirujanos de Anatolia especializados en aplicar procedimientos tan complicados, o si un conocimiento más generalizado de la medicina capacitaba a un mayor número de personas para realizar este tipo de delicada cirugía.

Parece probable que hubiera algunos especialistas capacitados para administrar una forma de tratamiento tan invasiva y arriesgada. Pero dada la naturaleza igualitaria de la sociedad de Çatalhöyük y su aparente rechazo a las clases sociales, es concebible que la experiencia médica se compartiera tan ampliamente como las herramientas y la cultura de la ciudad.

La trepanación puede parecer un procedimiento primitivo. Pero esta forma de cirugía más antigua en realidad se utilizó durante miles de años, comenzando en el período Neolítico (10.000 a 4.500 a. C.) y continuando en varios lugares hasta el siglo VII d. C. (al menos).

Parece obvio que la práctica de la trepanación no se habría utilizado durante tanto tiempo a menos que mostrara cierta eficacia como forma de tratamiento. De hecho, la trepanación representa una versión menos desarrollada de un procedimiento médico moderno conocido como craneotomía, en el que se corta quirúrgicamente una sección del cráneo y luego se extrae temporalmente para aliviar la presión o eliminar el exceso de líquido del cerebro.

Si bien aparentemente podría usarse para tratar muchas afecciones preocupantes, la trepanación conllevaba un claro riesgo de muerte y probablemente se habría utilizado sólo como último recurso. Un joven que vivió en Çatalhöyük en el año 6.500 a.C. no sobrevivió al procedimiento, pero es probable que muchos otros anatolios sí lo hicieran e incluso mostraran signos de recuperación de sus condiciones, lo que explicaría por qué la práctica de la trepanación siguió siendo popular en la antigua Anatolia durante miles de años. de años.