Researchers have analyzed the chemical makeup of the tools used to create the big stone sculptures and found evidence that Easter Island’s society was sophisticated and its people shared information and collaborated.

“The idea of competition and collapse on Easter Island might be overstated,” says lead author Dale Simpson, Jr., an archaeologist from the University of Queensland. “To me, the stone carving industry is solid evidence that there was cooperation among families and craft groups.”

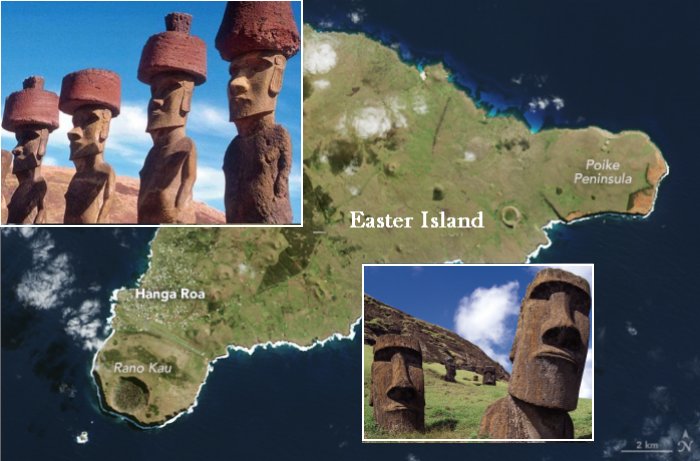

Easter Island is a remote island of the coast of Chile with baffling statues (moai) often referred to as “Easter Island heads.” The first people arrived on Easter Island (or, in the local language, Rapa Nui) about 900 years ago.

“The founding population, according to oral tradition, was two canoes led by the island’s first chief, Hotu Matu?a,” says Simpson, who is currently on the faculty of the College of DuPage. Over the years, the population rose and formed the complex society that carved the statues Easter Island is known for today. These statues, or moai are actually full-body figures that became partially buried over time. The moai, which represent important Rapa Nui ancestors, number nearly a thousand, and the largest one is over seventy feet tall.

Simpson says that “the size and number of the moai hint at a complex society. “Ancient Rapa Nui had chiefs, priests, and guilds of workers who fished, farmed, and made the moai. There was a certain level of sociopolitical organization that was needed to carve almost a thousand statues.”

During recent excavations of four statues in the inner region of Rano Raraku, the statue quarry, researchers took a detailed look at twenty-one of about 1,600 stone tools made of basalt that had been recovered. About half of the tools, called toki, recovered were fragments that suggested how they were used.

There are at least three different sources on Easter Island that the Rapa Nui used for material to make their stone tools. The basalt quarries cover twelve square meters, an area the size of two football fields. And those different quarries, the tools that came from them, and the movement between geological locations and archaeological sites shed light on prehistoric Rapa Nui society.

The team made the chemical analysis of the stone tools and the results pointed to a society that Simpson believes involved a fair amount of collaboration.

“The majority of the toki came from one quarry complex—once the people found the quarry they liked, they stayed with it,” says Simpson. “For everyone to be using one type of stone, I believe they had to collaborate. That’s why they were so successful—they were working together.”

“There’s so much mystery around Easter Island, because it’s so isolated, but on the island, people were, and still are, interacting in huge amounts,” says Simpson and according to him, “this level of large-scale cooperation contradicts the popular narrative that Easter Island’s inhabitants ran out of resources and warred themselves into extinction.”

While the society was later decimated by colonists and slavery, Rapa Nui culture has persisted. “There are thousands of Rapa Nui people alive today—the society isn’t gone,” Simpson explains.

“The near exclusive use of one quarry to produce these twenty-one tools supports a view of craft specialization based on information exchange, but we can’t know at this stage if the interaction was collaborative,” said Jo Anne Van Tilburg of Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, UCLA and director of the Easter Island Statue Project.

“It may also have been coercive in some way. Human behavior is complex. This study encourages further mapping and stone sourcing, and our excavations continue to shed new light on moai carving.”