I was going to write in a rather scholarly mode about my visit to the Tarim mummies, but I think all my “scholarly” has been temporarily burned out of me by my intensive month or so of thesis writing. I’ll have to write about that too at some point — what a trip that was! -but for now I’m going to just ramble on about the lovely weekend trip to the Bowers Museum and its amazing Secrets of the Silk Road display. This exhibition closes on July 25th, so if you get a chance to see it, hurry!

The Tarim mummies… goodness, where do I possibly start?! It’s one thing to write about a marvelous archaeological discovery in my thesis, and think a bit wistfully how nice it would be to see someday — knowing full well the odds of my heading off to some far-away place in Russia or China are quite slim. It’s absolutely another thing entirely to stand there, almost choked up as I stare down in awe at the actual body of this infant, or this woman — both of whom lived almost four thousand years ago. I feel a connection between us, even if it is merely in our shared human mortality.

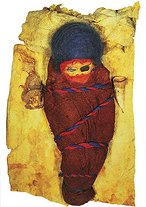

There is another connection between myself and the baby in particular, which is why I feel slightly choked up while studying her: I know her story. It is not mentioned in the display signage — curiously, even her true gender is not mentioned — but from reading books I know at least part of what happened to her.

There are two excellent books which discuss her, as well as the other astonishing finds in the Tarim Basin: The Mummies of Urumchi by the renown scholar and textile expert Elizabeth Wayland Barber, and The Tarim Mummies

by J.P. Mallory and Victor Mair. Both books relate with awe the astonishingly fine condition of some of these mummies: tall (over 6′), fair-skin that was only slightly weathered, with full heads of hair and beards, dressed in brightly colored and still intact clothing. Two of the finest mummies are a woman and a man from a pit grave which held them both, as well as two other women. The current assumption is that these graves contained lineages; therefore all four were related in some fashion either through blood or marriage. They were all buried at the same time, and from the lack of violence or damage apparent on the bodies, the scholars assume the group died of something like a particularly swift disease.

Buried above them, and thus at a later date, the archaeologists found the baby girl I got to see. She was maybe 8 to 10 months old at her death, and because she was buried in this particular tomb it is a good bet one of the women was her mother. From her grave goods it also seems clear whomever buried her cared very much about her, and tried very hard to keep her alive. For example, interred with her was the tip of a cow horn on her right, and the udder of a sheep on her left. As Barber writes so movingly in her book, it would seem every effort was made to continue to feed the infant, with the cow horn as a tiny cup to attempt to pour milk between her lips, and the sheep’s udder as a try at a primitive baby bottle.

Buried above them, and thus at a later date, the archaeologists found the baby girl I got to see. She was maybe 8 to 10 months old at her death, and because she was buried in this particular tomb it is a good bet one of the women was her mother. From her grave goods it also seems clear whomever buried her cared very much about her, and tried very hard to keep her alive. For example, interred with her was the tip of a cow horn on her right, and the udder of a sheep on her left. As Barber writes so movingly in her book, it would seem every effort was made to continue to feed the infant, with the cow horn as a tiny cup to attempt to pour milk between her lips, and the sheep’s udder as a try at a primitive baby bottle.

The family wore wool, which is not native to the area — so apparently they or others like them brought wool-bearing sheep to that region. The baby girl wears two beautifully dyed felt bonnets that tie under her chin: a red one, and over that a blue one. The wool the felt is made from is a type of cashmere, which is both incredibly soft, and holds colors wonderfully — which means her bonnets are still brilliant and vibrant looking. From under the red bonnet framing her face you can just see a few wisps of her strawberry blonde hair. She’s wrapped warmly in a loose-weave blanket dyed a rich rusty red color, which has been snugly bound about her with a colorful piece of yarn made of two strands twisted together — one blue, the other red, just like with her bonnet.

Laid over each eye are two tiny pieces of bright blue or blue-green stone. These are remarkable for a number of reasons. There is speculation that the stones are the color of the baby’s eyes — blue — which becomes part of the marvelous mystery of these ancient and clearly Caucasian mummies located in China. Further, these stones are not native to the area. They had to be brought in at some point, which also means they were deliberately chosen to be interred with this baby — like a precious gift given to someone beloved who is departing.

The baby is a tiny little thing as I stare down at her in the darkened room. I cannot help but wonder which of the buried three women was her mother. It had to be one of the two that were not well preserved, since the female that mummified well was older, and no one has mentioned any signs of being a lactating mother on her. Of those two, was it the one off on her own in the northern end of the tomb? Or was it the one curled next to the well-mummified female? Is the infant the daughter of the man who was there, as is widely presumed? What sort of family did they have; did they all care for her, cuddle her, sing her to sleep as they traveled? How old was she when her entire family died, and how long were the kind-hearted natives able to keep her alive?

Why would the Cherchen baby’s family bring such a tiny infant to such an inhospitable area? What was their goal; why did they travel so far from any others who looked like them? The burial was found in the Tarim Basin, near Cherchen. Tarim is on the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert, and according to one of the museum docents, “Taklamakan” translates literally as ”go in and you don’t come out.”

So many questions, such an intriguing mystery; I want to know, and I don’t know how to find out.